24 HEURES : ce-que-la-machine-a-ecrire-navait-pas-encore-dit, par Florence Millioud-Henriques

RTS : Frédéric Clot expose son univers pixelisé à Neuchâtel, par Florence Grivel

24 HEURES : figuratif-frederic-clot-foltre-espacetemps-pixel, par Florence Millioud-Henriques

Arc Info : jungle-de-pixels, par Camille Jean Pellaux

Mousse magazine : Memoria del sublime il paesaggio nel secolo XXI” at Museo Villa dei Cedri, Bellinzona, par Share

EXHIBITIONS

“Memoria del sublime il paesaggio nel secolo XXI” at Museo Villa dei Cedri, Bellinzona

Part of our natural and cultural patrimony, landscape art tells the story of our time: humanity’s relationship with nature, and how architectonic transformations and technological advances have modified the environment we live in, changing the way we perceive it. Landscape also materializes our physical sensations and our spiritual yearnings.

Artists in both the past and the present have viewed it, more than anything else, as a creation of the mind, a fragment of intimacies. Art’s response to urgent environmental questions has been to return to the Romantic perception of nature and, to a degree, to the sense of the Sublime – that form of innamoramento with the world around us, together with an awareness of its fragility and, at the same time, its disquieting power. In our contemporary era, the sublime no longer speaks to us of elevated thoughts and feelings, rather it sets forth the full extent of the existential threat we face, of the fracture in the relationship between humanity and nature. Landscape becomes pure utopia once again.

What is a landscape? Fundamentally symbolic for the Middle Ages, landscape would become an aesthetic experience in the writings of Petrarch, in 1330. In painting, landscape art gained widespread recognition in the 16th Century with Leonardo da Vinci and the Venetian Giorgione. Having become “classical” in the 17th Century with Nicolas Poussin, landscape acquires a nostalgic dimension in the Romantic period – thereby renewing the poetic tradition of Ovid and Virgil. The perception of nature is not restricted to a here and now, to the representation of a portion of the lived, observed world, but is open to a beyond that transcends all human reality. This is the unattainable horizon before which the solitary traveller in Caspar David Friedrich’s famous painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818, Kunsthalle Hamburg) meditates. Throughout the 19th Century, accordingly, as the march of industrialization leads to a society avid for entertainment and tourism, this cleft between nature and utopia becomes more apparent: nature is no longer merely a resource but becomes a consumer object – the Swiss Alps, the German forest and, later, the exotic landscapes of South America and Africa. These “icons” henceforth are an integral part of the collective imagination and they remain familiar tropes in advertising and the promotion of tourism.

Contemporary artists have responded in their own way to this historical drift, as we see from the works in Julian Charrière’s Panorama (2011–2012) series, from Christiane Baumgartner’s woodcuts of the German forest (Deutscher Wald, 2007), and from Didier Rittener’s engaging collection of drawings Libres de droits (2018–2019). Here, the erasure of the subjects in exotic or continental panoramas lays bare the landscape’s construction mechanisms, by removing a pirogue on a South American river, the shore becomes an unexceptional European lakefront. Furthermore, these views leave no doubt about how the colonization of nature is to be defined and in this sense they resonate uncannily with the views of the Swiss Alps in Stefania Beretta’s Montagne violate (2012) series or those of the “virgin” forest on the island of Singapore in Monica Ursina Jäger’s Shifting Topographies (2018–2019). Marco Scorti’s infinitely adjustable landscapes, like Christiane Baumgartner’s “scarified” forests, expose the full extent of the existential and cultural fracture in the relationship between humanity and nature.

“What began as a rift, in the early 19th Century, had expanded, by the start of the 20th Century, into nothing less than a radical, irreversible breach in the relationship between human beings and nature, and is today a crisis scenario concerning not only nature in itself but also the possibilities for perceiving and representing it.” (Reinhard Spieler, “L’expérience de la nature entre bonheur pur et scénario de crise [The Experience of Nature: from Rapture to Crisis Scenario]”, in the exhibition catalogue).

Nature and artifice

Today, artists not only perceive and conceive the artifice behind any representation of nature but also make it, literally, their subject. Vaud-born Frédéric Clot’s “biotopes” are an eloquent illustration of this: his representations of fruit and plants, interwoven with computer data and governed by a digital aesthetic, are more evocative of a greenhouse in a strange botanical garden than of nature preserved in the wild. It is from this interaction between the scientific and artifice that the contemporary sublime emerges. The photographs shot in the light of the full moon by British photographer Darren Almond, like German artist Mariele Neudecker’s sculptures with their chemical fog, re-establish via technique a link with the Romantic works of Caspar David Friedrich. The blurs and reflections of Axel Hütte’s digitally untreated analog photographs generate pictorial atmospheres that recall not only Friedrich but also J. M. W. Turner. In the landscapes of Quayola’s digital pictures, meanwhile, the line between figuration and abstraction is smeared by means of image analysis software and manipulation by computer algorithms. Quayola’s landscapes become impressionistic, reminding us that the Impressionists were seeking precisely to represent only the pictorial characteristics of nature, or, in other words, colour and time.

It is time indeed that is at the heart of Annelies Štrba’s coloured flowers, a metaphor for nature and the cycle of life; and, likewise, at that of the almost conceptual landscapes of Janaina Tschäpe’s recent compositions – interiorizations of time spent contemplating a landscape. This malleability of the landscape as matter is crucial to any reading of Ester Vonplon’s photographs. With Andrea Gabutti’s waterfalls and their almost expressionistic strokes, we return to landscape as personal experience, a fragment of intimacy. Claudio Moser’s vistas of the Negev desert under the midday sun reconnect the physical experience of a particular landscape with its representation. Finally, the question of time’s fluidity, of the ephemeral, contained in Alain Huck’s work also holds out hope of a reconciliation, of a return to origins “when all the energy of societies and human beings, their bodies, too, will be immersed in the inexhaustible mineral and vegetal elements, matter and air”. And in among the mysteries of mineral matter is exactly where, via a computer simulation, Alain Bogana allows us to conceive a landscape of our own.

At Museo Villa dei Cedri, Bellinzona

Until 4 August 2019

Seniorweb : Schweigen und Stille, par Fritz Vollenweider

24.06.2019 - Fritz Vollenweider

Schweigen und Stille

Eine reichhaltige Sommerausstellung im Genfer Musée Rath lotet die Vielfalt der Stille in der Kunst aus.

Besonders vielseitig und in mancher Hinsicht einmalig ist die Zusammenstellung von Werken verschiedener Epochen, vielseitiger Stilrichtungen und zahlreicher Künstler, die bis Ende Oktober im Genfer Musée Rath zu sehen ist. Das Thema ist sowohl im deutschen wie im französischen Ausstellungs-Titel formuliert: «Schweigen und Stille» – «Silences». Diese sprachliche Einfachheit sollte nicht über die vielschichtigen Verknüpfungen und die Komplexität des Themas hinwegtäuschen.

Den Rundgang von Abschnitt zu Abschnitt begleitet die Erinnerung an einen Satz von St. Exupéry: «Stille des Menschen, der sich aufstützt und nachdenkt, der fortan ohne Aufwand empfängt und dem Gehalt seiner Gedanken eine Form gibt» (Aus Citadelle, deutsch in Auszügen u.a. im Bändchen Die Botschaft der Wüste des Verlags Die Arche, Zürich, o. J.)

Denkbar, dass die verschiedenen Maler der verschiedenen Stile und Epochen gerade in solcher Stille die Inhalte und Formen ihrer Werke gefunden haben. Lada Umstätter, die Kuratorin, hat augenscheinlich mit ähnlichem Bemühen um den Gehalt und die themabezogene Aussage des Ganzen die Konzeption erarbeitet und verwirklicht. Alles beeindruckt und überzeugt: Die einzelnen Kunstwerke als solche, ihre spannende Gegenüberstellung in den Ausstellungsräumen und die grosse Klammer der gesamten Ausstellung – eben als «Hymne an die Stille» im Sinne des feinsinnigen französischen Dichters. (a.a.O.)

Frédéric Clot (1973): Lisière et cabane, 2010. Crayon de graphite sur papier 1100×1800 mm. Inv. D 2011-0027. © Cabinet d’arts graphique du MAH, Genève.

Das Thema der Ausstellung beabsichtigt nicht, den Begriff «stumme Dichtung», mit dem die Malerei in der Antike bezeichnet wurde, zu belegen oder gar zu illustrieren. Schon seit langen Jahren und mit vielfältigen Entwicklungen und Varianten der Stile wirkt die bildende Kunst zuzeiten schreiend, fordernd, lärmig – alles andere als stumm. Und Stille hat gar nichts, Schweigen nur teilweise mit Stummsein zu tun. So trägt den auch das erste Segment der Schau das Motto «vom Lärm zur Stille». Es zeigt unter anderem Jagdhunde, die über ein Wildschwein herfallen (Johannes Fijt, 1611-1661, Chasse au sanglier), eine Gesangsgruppe, eine Seeschlacht, andererseits auch eine Frau, die sich das Reden versagt.

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), Melancholie, 1514. © Cabinet d’arts graphiques du MAH, Genève. Bild A. Longchamp.

Insgesamt zehn solche thematischen Abschnitte enthält die Schau. Darunter selbstverständlich das «Stille Leben» (nicht von ungefähr französisch «nature morte» geheissen), «Ungesagtes», «Sakrale Stille» (mit Elementen der Kontemplation und Meditation), «Eitelkeit», «Melancholie» (Albrecht Dürer und Felix Valloton), «Poesie der Stille», «Stille Landschaften» (von Calame, Mont-Rose bis Frédéric Clot, Lisière et Cabane) «Räume der Stille» (Simon Edmondson, Palace, 2015) und schliesslich «Partituren der Stille» (Adolphe Appia, 1862-1928, Décor pour Iphigénie en Aulide de Gluck, 1926)

Den Weg durch die Ausstellung begleitet ein handlicher Führer in französischer Sprache, der einzelne Werke kommentiert und die Bedeutung, die gestalterische Absicht der Sektoren auch, kurz und verständlich kommentiert. Trotz der lediglich 67 A5-Seiten entnimmt man dem schmalen Bändchen eine Fülle von Anregungen beim Schauen und auch beim Verarbeiten der Thematik und ihrer zahlreichen künstlerischen Verknüpfungen. Die Ausstellung sozusagen mit nach Hause nehmen kann man mit dem grossformatigen Katalog von 207 Seiten Umfang. Einige Abschnitte davon sind schon im Führer aufgeführt. Darüber hinaus bietet das umsichtig konzipierte, mit gründlicher wissenschaftlicher Akribie von zahlreichen namhaften Fachleuten realisierte Werk eine Fundgrube sowohl für wissenschaftliche Studien als auch für eine mehr alltägliche Vertiefung des lebendig und eindrücklich verwirklichten Ausstellungsthemas.

Auch für diese Publikationen zeichnet Lada Umstätter, die Chefkonservatorin der Musées d’art et d’histoireverantwortlich. Zusammen mit weiteren Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeiter ist ihr mit SILENCES wahrlich ein beglückendes und anregendes Gesamtkunstwerk gelungen. Nicht unbeteiligt daran war die Bereitschaft vieler institutioneller und privater Leihgeber; sie sind in den Publikationen aufgeführt. Sie halfen mit, dass man Bilder zu sehen bekommt, die man noch nie gesehen hat und nie wieder sehen wird.

Im Musée Rath, Genf, bis 27. Oktober 2019

CACY : Slow numérique, par Karine Tissot

Le Temps : Des trésors d’artistes enfouis sous le futur Musée cantonal des beaux-arts de Lausanne, par Elisabeth Chardon

Arc Info : les-vestiges-aseptises-de-frederic-clot, par Séverine Cattin

Espace 2 : La tête à l'envers, par Marlène Métrailler

Le Temps : Le peintre Vaudois Frédéric Clot, par Laurence Chauvy

Wall Street International : Frédéric Clot, par Simon Baur

5 APRIL 2013

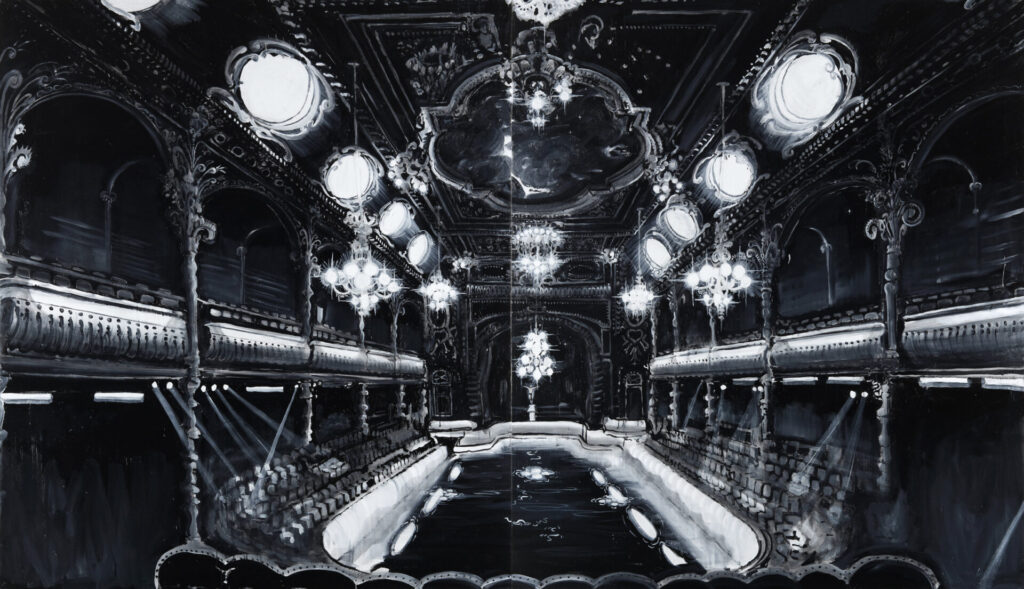

Le Grand Théâtre, 2012, Oel auf Leinwand, 180 x 320 cm. Crossinvest collection, Lugano

Die Wildnis irgendwo im Amazonas, ein Take-away abseits der Strasse, die oberen Ränge des Grand Theâtre, eine Fabrikhalle, Landschaften und Menschen. Frédéric Clot schreckt vor keinem Thema zurück. Er malt sie alle und – das zeigt seine Malerei selbst – es muss schnell gehen. Geschwindigkeit ist eine der Qualitäten von Frédéric Clots Bildern; sie malerisch umzusetzen, ist kein leichtes Vorhaben, doch hat er hierfür eigene Verfahren entwickelt. Was hat man sich darunter vorzustellen? Seine Bilder zeugen nicht von Unsorgfalt, seine Kompositionen sind überlegt, ich bin versucht zu sagen, sie sind einstudiert, erprobt, verworfen und wieder neu versucht. Sie sind vom Gegensatzpaar „Geschwindigkeit und Innehalten“ geprägt, eine Art barocke Struktur von Leben und Vergänglichkeit taucht darin auf. Es scheint, als habe der Künstler unentwegt seine eigene Endlichkeit vor Augen. Und wie diese ein Grund zum Schreiben sein kann, so ist sie sicher auch ein Grund, Bilder zu malen. […]

Überhaupt werden in den Bildern von Frédéric Clot selten Fragen gestellt und auch keine beantwortet. Vielmehr werden Zustände aufgezeigt und konstatiert. Darin liegen ihr Potential und ihre unglaubliche Tragik. Sie zeigen das Leben, wie es ist und vor allem, wie wir es uns vorstellen. Die Dämonen an der Decke des Kirchenschiffes, das Unheimliche eines Kiefers im Wald, die Furcht vor einem verlassenen Haus in der Pampa, sie alle sind Erfindungen und Ausgeburten unserer Gedanken und Fantasien. Und es ist die Erinnerung, die es uns ermöglicht, eine entsprechende Erfahrung, Begegnung oder Beschreibung so heraufzubeschwören, dass sie uns in Irritation versetzt. Dass sie nur andeutet und dadurch bei der Betrachterseite einiges bewirkt, darin liegt die Macht der Bilder von Frédéric Clot. In flüchtigen Kompositionen und unter Verwendung weniger und fast immer gleich bleibender Farben deutet er die Ereignisse an, setzt sie auf die Leinwand und überlässt sie dem Betrachter.

Im Galerie Carzaniga, Basel. 23. März – 4. Mai 2013

Le Temps : Le couteau dans la plaie des images, par Laurent Wolf

Arcinfo : D'Alberto Giacometti à Frédéric Clot, par Séverine Cattin

RTS : Hors-Bord

Le Temps : Sept d’un coup pour deux tailleurs d’images et de mots, par Isabelle Ruf

Cultureactif, «Hors-Bord», Arnaud Robert et Frédéric Clot, par Francesco Biamonte

CCSParis : Le Phare

La Tribune de Genève : La série «Hors-bord» bouscule le livre d’art

LE TEMPS : «Hors-Bord: images proliférantes», par Laurent Wolf

LE COURRIER : «Voyages en outre-monde», par Anne Pitteloud